Two discoveries from the age of the dinosaurs along with a more recent one that straddles the borderline between paleontology and anthropology headline this post. As usual I begin with the oldest and work forward in time.

England’s southern coast is one of the most famous and important fossil areas in the world, in many ways that is where the very science of paleontology got it’s start. At the eastern end the ‘White Cliffs of Dover’ are made of chalk from the cretaceous period, indeed the whole cretaceous period is named for the Latin word for chalk because of those cliffs. The west end of England’s south coast is also well know for it’s fossils from the Triassic period, the dawn of the age of the dinosaurs.

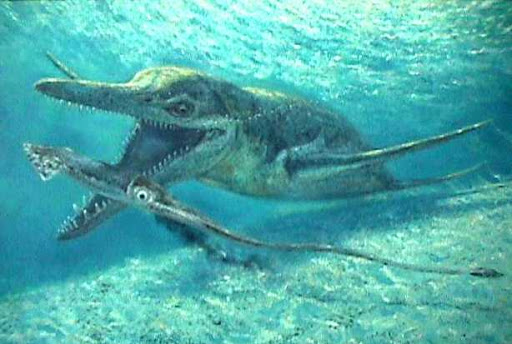

It’s the middle of the southern shore, the co-called Jurassic coast that includes the Isle of Wight that is most famous for its fossils however. It’s here that during a walk along the water’s edge that fossil enthusiast Phil Jacobs noticed the tip of a snout lying on the ground beneath a cliff. Realizing that the snout must have just eroded out of the cliff face Jacobs secured the bones and quickly got his friend Steve Etches to help him see if there were more of the animal’s bones still in the cliff. Thus they began a difficult and dangerous excavation that took several months but by the end the two fossil hunters had succeeded in finding a 2 meter long skull of a Pliosaur, the apex predator of the Jurassic oceans some 150 million years ago.

Although the fossil still has to be thoroughly studied in detail it appears that the skull is the most complete ever found of a Pliosaur and based upon the size of the skull in life the animal would have been 10-12 meters in length. The jaws contained 130 teeth, long and razor sharp and the muscle attachment points on the skull indicate that the creature could have had a biting force of 33,000 Newtons, twice that of a saltwater crocodile, the strongest bite in the world today, all in all a real sea monster.

And that skull will be revealed to the world in a BBC special, hosted by David Attenborough no less. The special is scheduled for New Year’s day in the UK and hopefully will be seen soon thereafter in the rest of the world. Best of all, Jacobs and Etches are certain that the rest of the animal is still in that cliff awaiting excavation. Maybe the money and notoriety generated by the special will enable them to dig out the rest of this extraordinary beast.

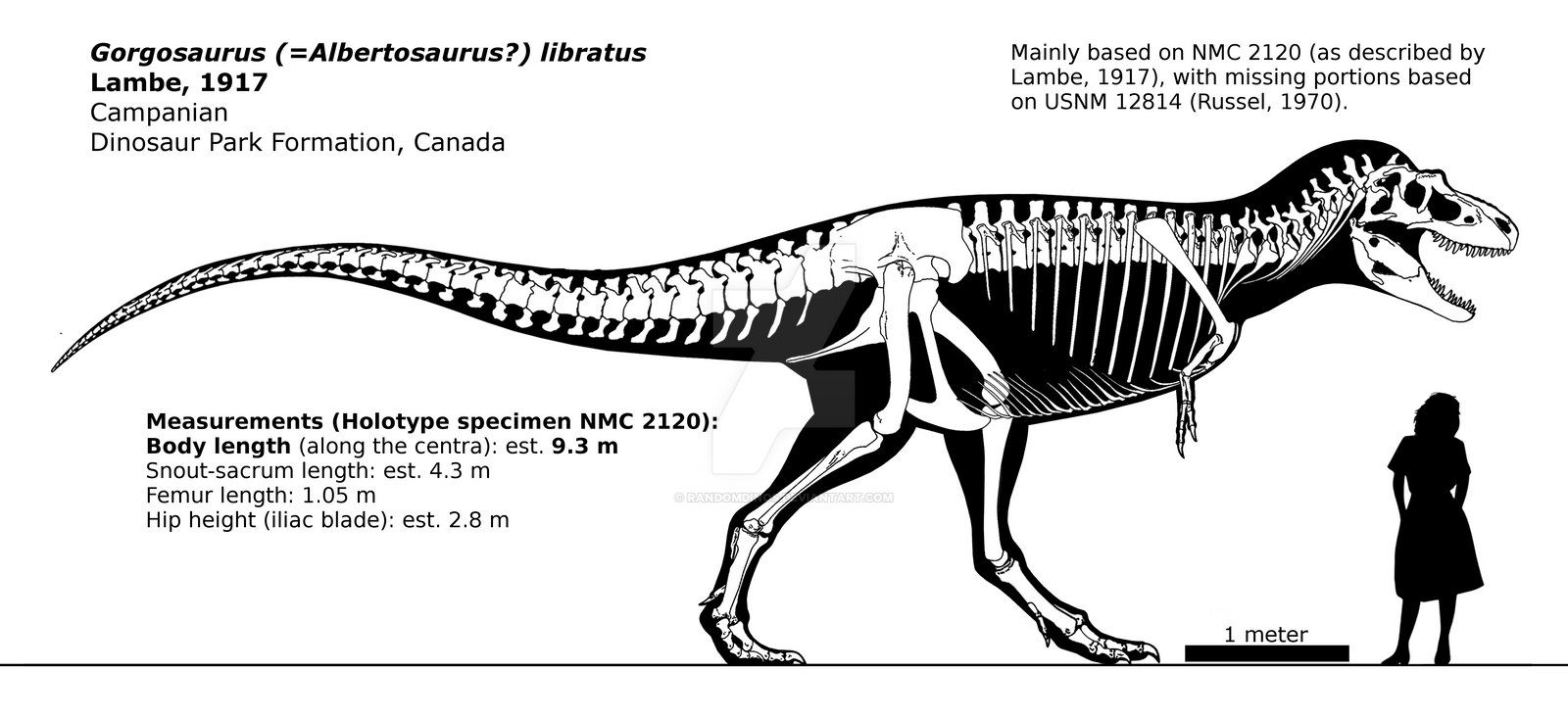

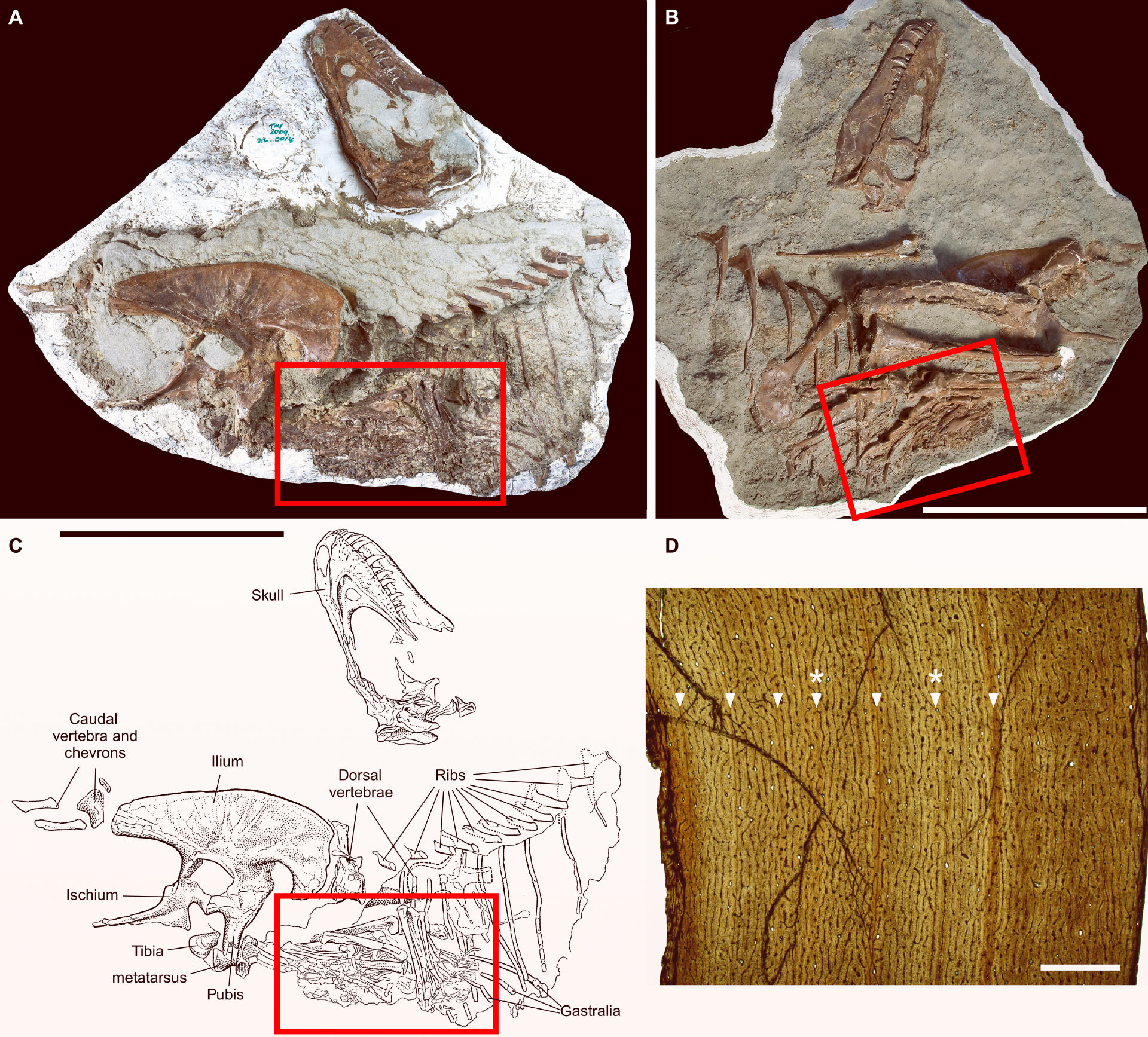

And speaking of apex predators paleontologists at the University of Calgary and the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology have announced the discovery of a juvenile specimen of Gorgosaurus libratus, a relative of the famous Tyrannosaurus rex, with the contents of its stomach, its last meals intact. The specimen itself is about 75 million years old and is thought to have been between 5 and 7 years old at its death. In life the animal would have weighed some 350 kg, stood as tall as a tall man while measuring more than four meters from its nose to the tip of its tail.

What makes this specimen so interesting however are the bones found inside the animal’s stomach, four drumsticks from another type of birdlike dinosaur called Citipes, each of whom would have been about the size of a modern turkey. The bones were articulated, in other words they hadn’t been broken up by chewing, and one pair appears to have been more digested than the other so they may be the animal’s last two meals. Also, there is no evidence for the rest of the bodies of the Citipes but it’s unlikely that a meat eater like G libratus wouldn’t have eaten the rest of its prey if it could.

Previous finds of young Tyrannosaurids have indicated that they were actually more slender, more agile and quick-footed than the bone crushing monsterous adults and the G libratus specimen fits in that picture. The animal’s last meal (s) also contributes to that idea because Citipes were rather small and fast animals themselves, so the young G libratus would have had to be a fast predator to catch them. A very different creature from the heavily muscled giants they grew up to be.

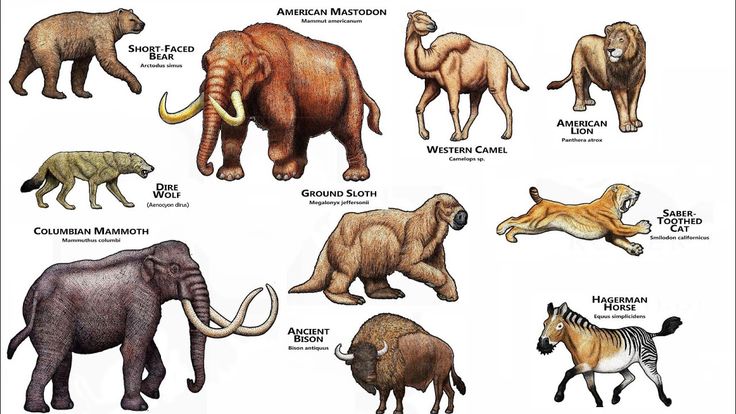

Finally today I like to discuss a new study from the Aarhus University in Denmark that lies on the border between paleontology and anthropology. The study considers again the question of what caused the extinction of the large ice-age mammals like mammoths, mastodons, cave bears, Irish elk and etc. As a group these animals are known as the mega-fauna which is defined as any species that weighs more than 44 kg when fully grown. For decades now the debate has raged over whether these species died out because of climate change, the ice ages, or were they hunted to extinction by our ancestors.

The study examined DNA from 139 large species still alive today such as elephants, rhinos, oxen, cattle, deer, kangaroos and even our cousins the great apes. What the researchers found was that over the last 800,000 years the populations of large animals had remained fairly stable even while the polar ice caps grew and then receded about every 100,000 years. Then, just about 50,000 years ago the populations of even those species that still survive showed a marked decline, at just the time when mammoths and the others went extinct. If the populations had stayed steady for over 700,000 years of climate change it is very unlikely that climate caused the sudden population loss.

More than that, the precise timing of the population drop always coincided with the period when archaeology indicates that the first humans entered the area. If correct it seems more likely than not that our species destruction of the environment isn’t a recent development but rather has been a part of our nature from the start.