‘Let’s put our heads together and see if we can’t come up with a solution,’ is a very human method of coming together, tossing out ideas and taking advantage of multiple points of view in an effort to solve very difficult problems. This idea of ‘Collective Intelligence’ is something uniquely human, one of the greatest advantages that we have over the mere animals with which we share our world.

Or maybe not! Turns out that there are many known cases of animals who work collectively in order to survive the dangers and difficulties life throws at them. Consider the prairie dog, a species of squirrel that inhabit the treeless plains of central North America and who live in ‘towns’ that can number several hundred individuals.

Whenever the town’s inhabitants go out to forage for food several of the older adults position themselves around the group standing watch, keeping an eye out for predators instead of finding food for themselves. Whenever a threat is detected the guards will sound the alarum, a series of calls so sophisticated not only do the other prairie dogs know whether the menace is coming from the ground, a coyote, or the air, an eagle, but the calls tell them from what direction! In fact the whole prairie dog system is so well arranged that those adults who are feeding know when it is their turn to stand watch so that their fellows who have been on guard duty can grab a bite. Numerous other examples in nature can be cited and now naturalists have uncovered another, similar type of collective intelligence in animals that are individually much less intelligent than a prairie dog.

It’s well known that ant colonies send out forager ants to search for sources of food. These foragers lay down a sent trail as they search both to enable them to find their way home but also to enable the other ants in the colony to find the food source they’ve discovered. Once the forger has alerted the colony to the presence of the food an entire army of worker ants will follow the sent trail and begin the process of bringing the food back to the nest.

What if however, something should happen to destroy the sent trail, a branch of a tree could fall across it or you might actually step on it. In that case, how do the ants find their way back home? Now naturalists at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel have set up an experiment in the lab to study just how, and how well ants solve such dilemmas. As Aviram Gelblum the lead author of the study put it. “We addressed this question by studying the cooperative transport of ants as they attempted to transport large loads through semi-natural environments.”

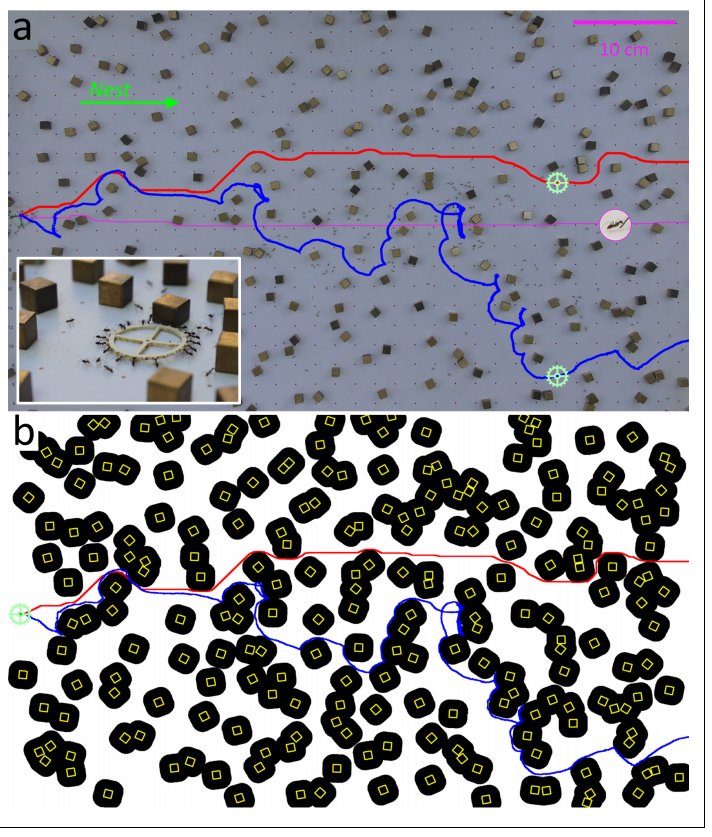

Using Longhorn crazy ants as their test subjects the researchers set up a labyrinth using cubes of the same size randomly spread across a surface separating the ant’s nest from a food source. The cubes were used to block the ant’s direct path home and force them into searching for an alternate route. The movements of the ants were tracked by image processing and compared to a computer program that mimicked a random walk in the direction of the nest.

What the biologists found was that the ants consistently outperformed the random method, and they did so by cooperating. You see in addition to the large number of worker ants who are carrying the loads there are a smaller number of leader ants who fan out from the column as far as a maximum distance of 10cm.

When faced with a blocked path the leader ants act as scouts searching for possible alternative paths and then coordinate with each other to steer the worker ants into the new chosen path. This process is repeated until the obstacle has been bypassed and the way back to the nest is clear. Having the leaders acting as scouts at a distance from the main group allowed the ants as a whole to significantly reduce the time spent searching for another way back home when their original path becomes blocked.

By putting our heads together in order to solve problems we humans have succeeded in building our civilizations. It’s hardly surprising therefore that other animals have also discovered the advantages of collective intelligence.