At birth we humans are perhaps the most helpless of creatures. Unable to move let alone find food or take care of ourselves in any way we are utterly dependent on other humans for our survival. For that reason the very first thing our brains are designed to do is recognize another person, especially another human face.

This instinct is true of virtually all mammals and birds, even some reptiles. Since the first thing we see after birth is usually our mother we imprint on her. And since humans have always lived in groups we quickly imprint on the other members of the group, our father, siblings, and other relatives.

It also very important that we be able to recognize the mood other people are in. Crying for food when your mother is angry, or perhaps frightened because a predator is near is more likely to get you a slap than a meal. The shape of a smile, or a frown, and what they mean also appears to be built into our brains even before we are born. And as we grow older we become attuned to the more subtle facial expressions the different members of our group have, this ability aids in our communications with those around us.

So important is our ability to detect and analyze another human face that we are unconsciously looking for human faces all the time, and all to often finding them in objects that are completely non-human. We’re all familiar with this psychological phenomenon; we’ve all at one time or another seen a human face in almost anything that vaguely resembles two eyes, a nose and mouth. Artists sometimes even toy with our mind by generating face like shapes out of things that are completely non-human.

Psychologically this phenomenon is called pareidolia and studies have shown that our minds will even attribute emotions to non-living objects if we see a face in them. Perhaps even stranger is the fact that the feeling of seeing a face, and emotions in that face will persist even after we realize our mistake and recognize that the thing we are anthropomorphizing isn’t even alive.

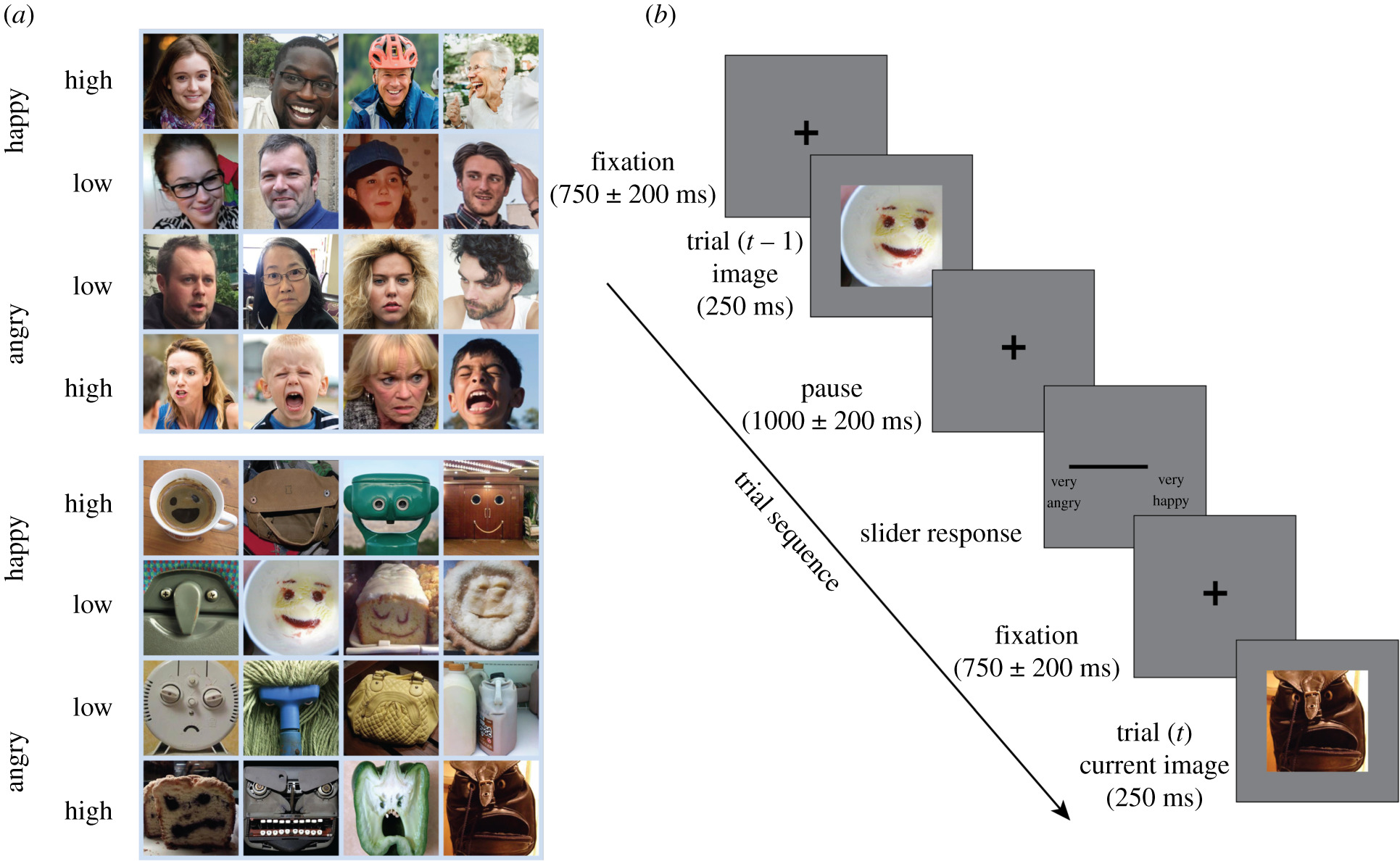

Now a new study by neuroscientists at the University of Sydney in Australia and the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda in Maryland has examined both how a pareidolia face is detected and how the ‘expression’ on that face is analyzed. In the experiment a group of 17 student volunteers were shown a sequence of images of both actual human faces and illusionary faces on non-living objects. Forty images of each type were used with the human faces expressing emotions ranging from happy to neutral to angry.

The students were shown the images alternating between human and non-living with each image being shown eight times for a total of 320 trials. Although each image was shown eight times the order of the images was randomized so that a non-living image would follow different human faces. The students were asked to rate the emotion of the faces on both the human and illusionary faces as they saw them.

What the researchers found was that the emotional rating of the non-human faces was profoundly influenced by the emotion on the face of the human image immediately preceding it. This result indicates that our brain detects and then analyzes false faces in exactly the same manner as it does an actual human face rather than discarding the detection as a mistake. In addition, by controlling the time that the volunteers saw each image the researchers were able to estimate that our brains require only a few hundred milli-seconds to analyze even a pareidolia face.

According to Professor David Alais of the University of Sydney’s school of Psychology and lead author of the study, “From an evolutionary perspective, it seems that the benefit of never missing a face outweighs the errors where inanimate objects are seen as faces.”

Which goes to show that our brains are already programmed with a variety of instincts and behaviors before we are even born, instincts and behaviors that may have served our pre-human ancestors well but some of which may actually be harmful in our modern world. We need to better understand the way our brains work if we are ever going to control the prejudices and impulses acquired by our ancestors millions of years ago.