‘Dead men tell no tales’ the saying goes but I think archaeologists would argue with that. Much of what we have learned about the past has been obtained by studying the mortal remains excavated from ancient graves and the material goods that have been interred with them. Two recently published papers illustrate this point rather well. I’ll begin with a story about the ‘Black Death’ in 14th century England.

Entering Europe through Sicily in October of 1347 the bubonic plague sweep across the continent, reaching the British Islands in August of 1348. In cities like London the disease was so deadly that people died by the thousands leading to an almost complete breakdown of social norms. So many died that the time honoured customs of Christian burial were abandoned and the plague’s victims simply thrown into mass graves, several of which have been discovered and excavated by archaeologists.

In rural areas however the death toll was somewhat lower, enough so that some of the usual customs for honouring the dead continued to be carried out. To date only one mass grave associated with the plague has been discovered in the English countryside and a recent study published in the journal Antiquity gives evidence that even in these troubled times the country folk still did what they could to show respect for their dead.

The mass grave was discovered in 2012 on the grounds of Thornton Abbey and contains the remains of 48 men, women and children of all ages. The location of the grave itself is curious because the local church, and its graveyard, is less than two kilometers away, so why weren’t the plague victims buried there? The researchers, led by Hugh Willmott of the University of Sheffield, speculate that perhaps the local priest and gravediggers had succumbed to the plague themselves so that the local people were forced to turn to the Abby’s monks for help.

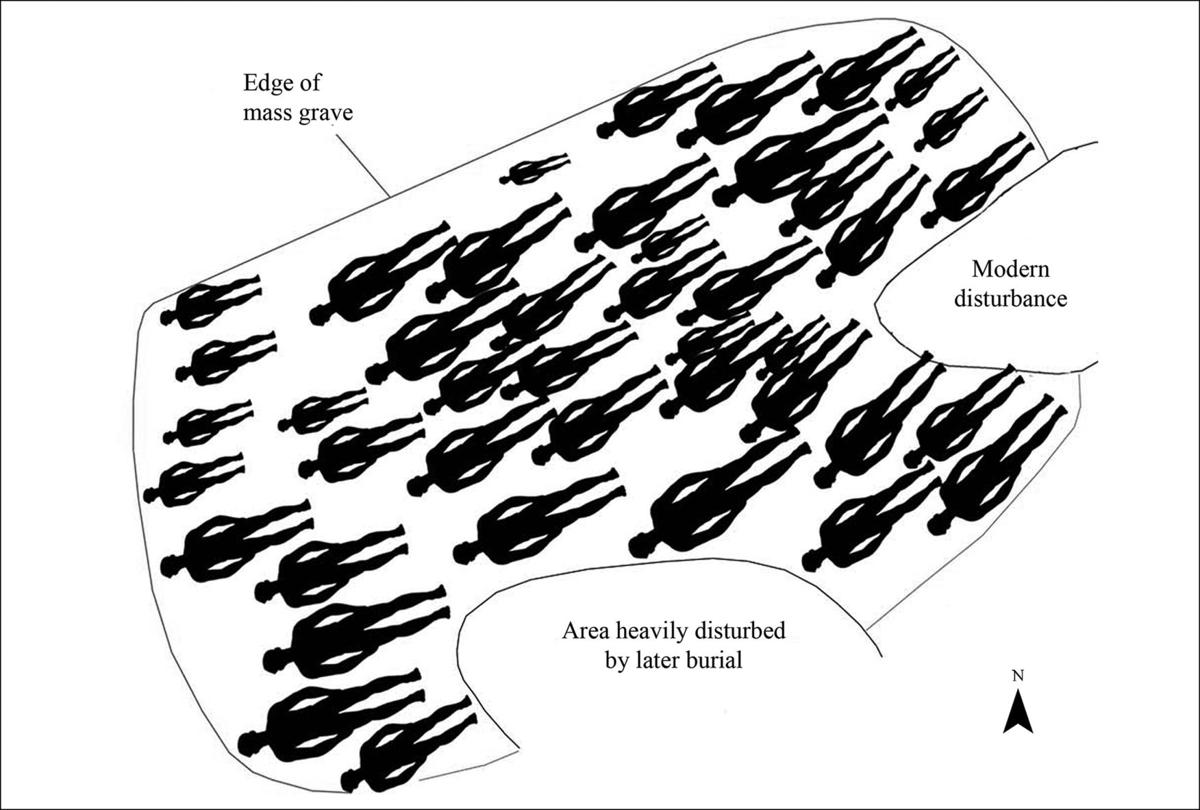

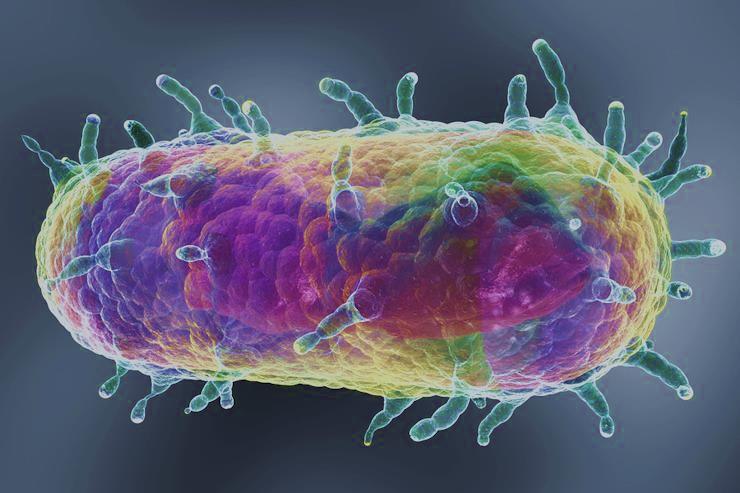

DNA analysis of samples taken from the molars of 16 individuals showed the presence of the bacteria Yersinia pestis, the germ that causes the bubonic plague. This leaves no doubt that the people buried in the mass grave died of the plague and were therefore highly infectious. Despite the danger however the dead bodies were not simply thrown into a hole in the ground. Rather each body was laid separately in a single layer of eight rows with no overlapping. There were even indications that each body had been covered in a shroud that had since decayed. The treatment of the dead shown at Thornton Abby is further evidence that even while it seemed that the world was collapsing around them people still did what they could to honour the memory of their departed loved ones.

Which brings up the question of just when did human beings first begin to perform burial rituals for their dead? And could it possibly have been before our species Homo sapiens ever existed? Turns out that there is growing evidence that Neanderthals also had burial rites that, if more primitive, nevertheless still seem very human.

The first such evidence came from excavations in a site in Iraqi Kurdistan known as Shanidar Cave. In the late 1950s and early 60s fragmentary remains of 10 Neanderthal skeletons were discovered in the cave. The big news however was the discovery of clumps of pollen adjacent to one skeleton that the researchers speculated could be the decayed remains of flowers that had been deliberately buried with the dead Neanderthals, a clear sign of some kind of funeral rite.

At the time that interpretation was very controversial. Critics counter argued that the pollen deposit was accidental, perhaps dropped by some animal. Neanderthals, it was thought, had little or no culture. After all cave paintings were made by Stone Age Homo sapiens, not Neanderthals. The earliest known examples of jewelry and carved figurines were again made by early H sapiens. Neanderthals may have had some stone tools and weapons but their societies were hardly more advanced than a troop of Chimpanzees.

Over the last several decades however evidence has mounted that Neanderthals did in fact have some culture, and even something resembling art. Cave markings have been found that are far too old to have made by H sapiens. Seashells and semi-precious stones have been discovered in connection with Neanderthal habitats that indicate they were used as decorations. Neanderthals it seemed were not as brutish as we’d assumed.

(Of course it’s worth noting at this point that the work of anthropologists like Jane Goodall over the last 50 years have shown that Chimpanzees also have a degree of what can only be described as culture, see my posts of 18Oct2017, 21Mar2018, and 16Mar2019.)

With the growing evidence supporting the funeral ritual interpretation of the burials found in Shanidar Cave you’re think that anthropologists would have returned to the cave in order to see if any further evidence could be found there. Trouble was that for about the last thirty years northern Iraq hasn’t been the safest place to do scientific research. After the recent defeat of the terrorist group ISIS however an archaeological team from Cambridge University returned to Shanidar in 2018 to reexamine the gravesite with the newest instruments and techniques.

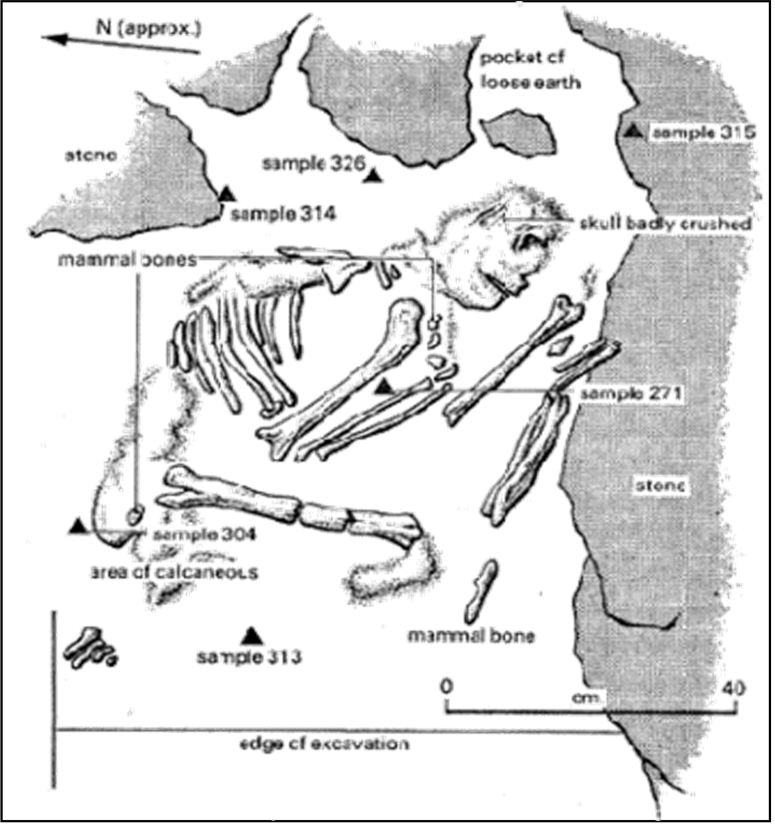

What the team unearthed were the skeletal remains of the upper body of a Neanderthal male, including the skull. The remains, which have been dated to 70,000 years ago, were lying on the person’s back with the left arm curled up so that the hand lay under the skull. Such a position indicates that the body had been deliberately arranged rather than simply thrown into a hole. There were also signs that the grave site for all of the bodies had been deliberately dug and it is possible that a large stone placed near the skull may have been intended as a headstone or marker or a sort.

These latest discoveries raise the possibility that the Neanderthals were using Shanidar as a graveyard, a special place for the burial of the dead. According to Emma Pomeroy, an archaeologist with the team. “If Neanderthals were using Shanidar cave as a site of memory for the repeated interment of their dead, it would suggest cultural complexity of a high order.”

The way humans care for, respect and remember their dead is one of the things that most makes us different from our animal relatives. This means that in a sense the dead can indeed speak, telling us much about what it is to be human.