Paleontologists surely must envy their colleagues the naturalists. Think about it, a naturalist can observe an animal in real life, in it’s natural habitat, actually seeing how that animal lives. They can even capture a specimen of the animal and dissect it to study its anatomy. Nowadays naturalists can even get a DNA sample of an animal in order to compare its genetic code to that of related species.

Paleontologists can’t do any of those things. With only a few fossils, often of only the hard parts of an animal, they have to figure out not only what kind of creature it was, its relation to other animals, but also how it lived, what it ate, everything about it. If new fossil evidence comes to light paleontologists often have to change their ideas, even about creature that have been known for many years.

There have been some major discoveries made in recent months concerning several extinct animals that have been known and studied for over a century. In this post I’ll be discussing several of these new finds. As usual I will start with the oldest and work my way forward in time.

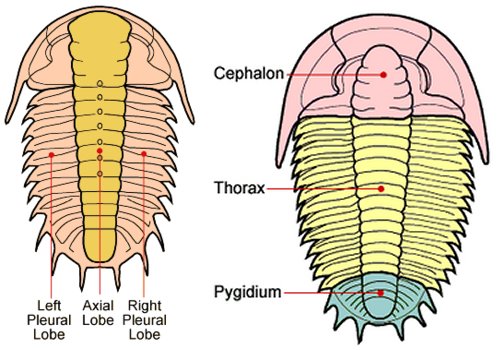

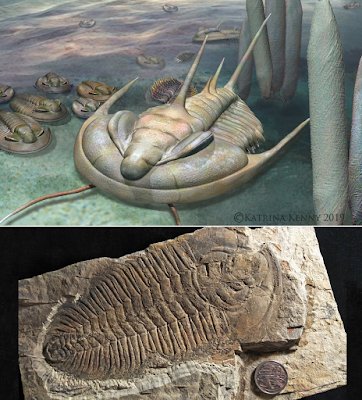

After dinosaurs I suppose that trilobites are the best known type of extinct animals. Trilobites were one of the first animals to develop a hard shell and because of that the Cambrian period, the earliest well recognized period of multi-cellular life, is often called the age of the trilobite. Not only were trilobites easily fossilized but they were both numerous, about 6,000 different species are known, and they lasted some 270 million years. That means there are a lot of trilobites in every paleontologist’s collection, professional or amateur.

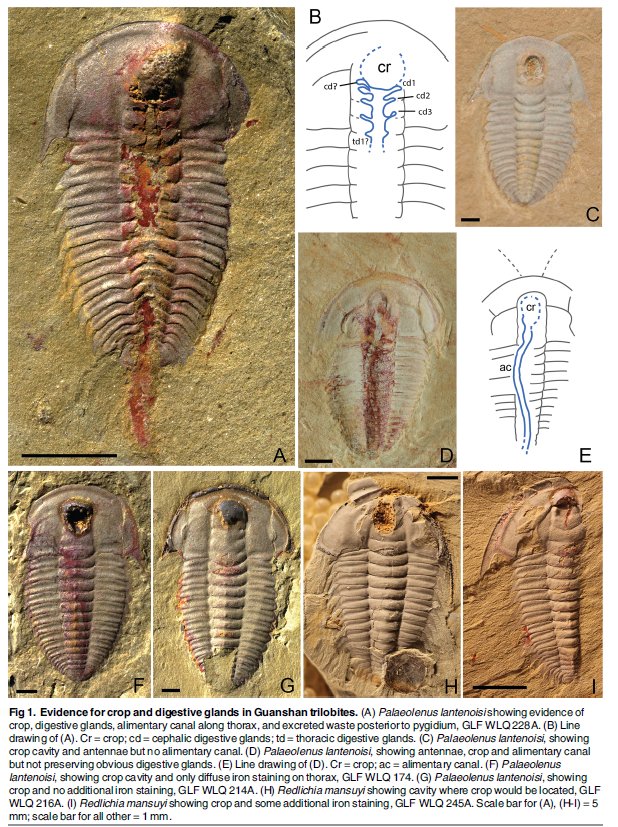

While the hard parts of trilobites, their shells are well preserved their internal anatomy rarely is. So paleontologists are always on the lookout for fossil sites that do preserve the soft parts of any species. Recently exceptionally preserved trilobite fossils have been discovered at a rock formation in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco in North Africa.

According to geologist Robert Gaines at Pomona College in Claremont, California what happened was that a nearby volcano erupted in a pyroclastic flow, similar to the one that buried Pompeii. In this case however the hot ash flowed onto the ocean where it quickly cooled before sinking to the bottom. The now cooled ash buried the trilobites alive in a sterile environment, one where bacteria could not cause the soft parts to decay. The ash then preserved much of the trilobite’s internal anatomy for millions of years. While the researchers hope to find many more specimens of well-preserved trilobites at the Morocco site their study has already confirmed one aspect of trilobite eating that had been conjectured for many years, trilobites chewed their food with the same legs they walked with.

That’s not as weird as it sounds because the jaws of all arthropods are actually modified legs. That’s what makes a close-up video of a grasshopper or an ant eating look so strange, they chew from side to side rather than up and down because they chew with legs that have evolved into jaws.

As one of the most primitive arthropods, trilobites did not have specialized legs so they actually chewed with the same legs they walked with before using those legs to then pass their food to their mouth. These fossils therefore not only tell us a lot about how trilobites themselves lived but also about how arthropods, the largest phylum of animals there is, developed their mouths and jaws.

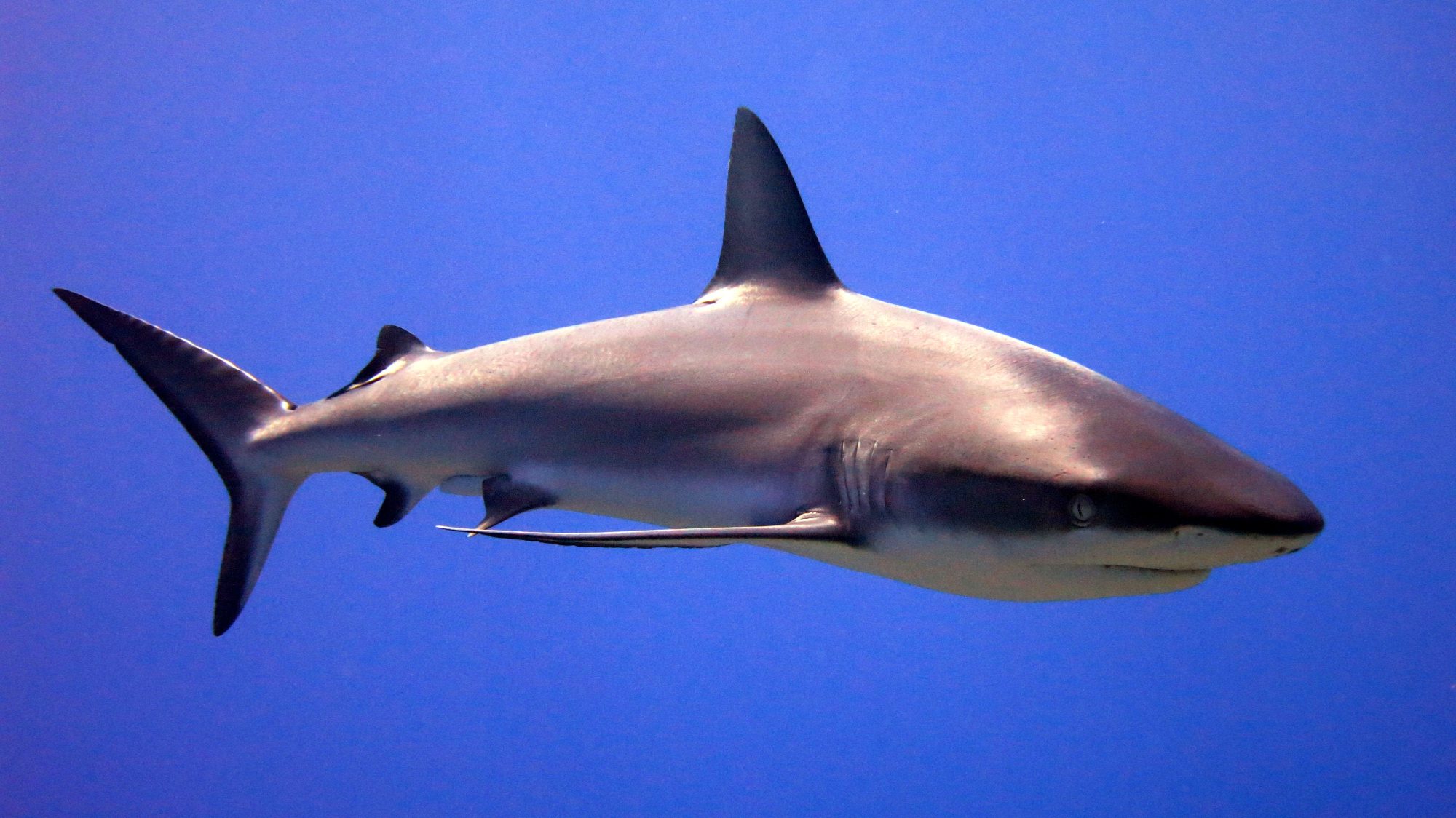

Almost two hundred million years after the first trilobites crawled on the ocean floor our ancestors the fish were developing their jaws. This was the Devonian period and the arrangement we have now of jawbone and teeth was not the only experiment that was tried. In fact there was a whole family of fish whose entire head and torso were covered in bone.

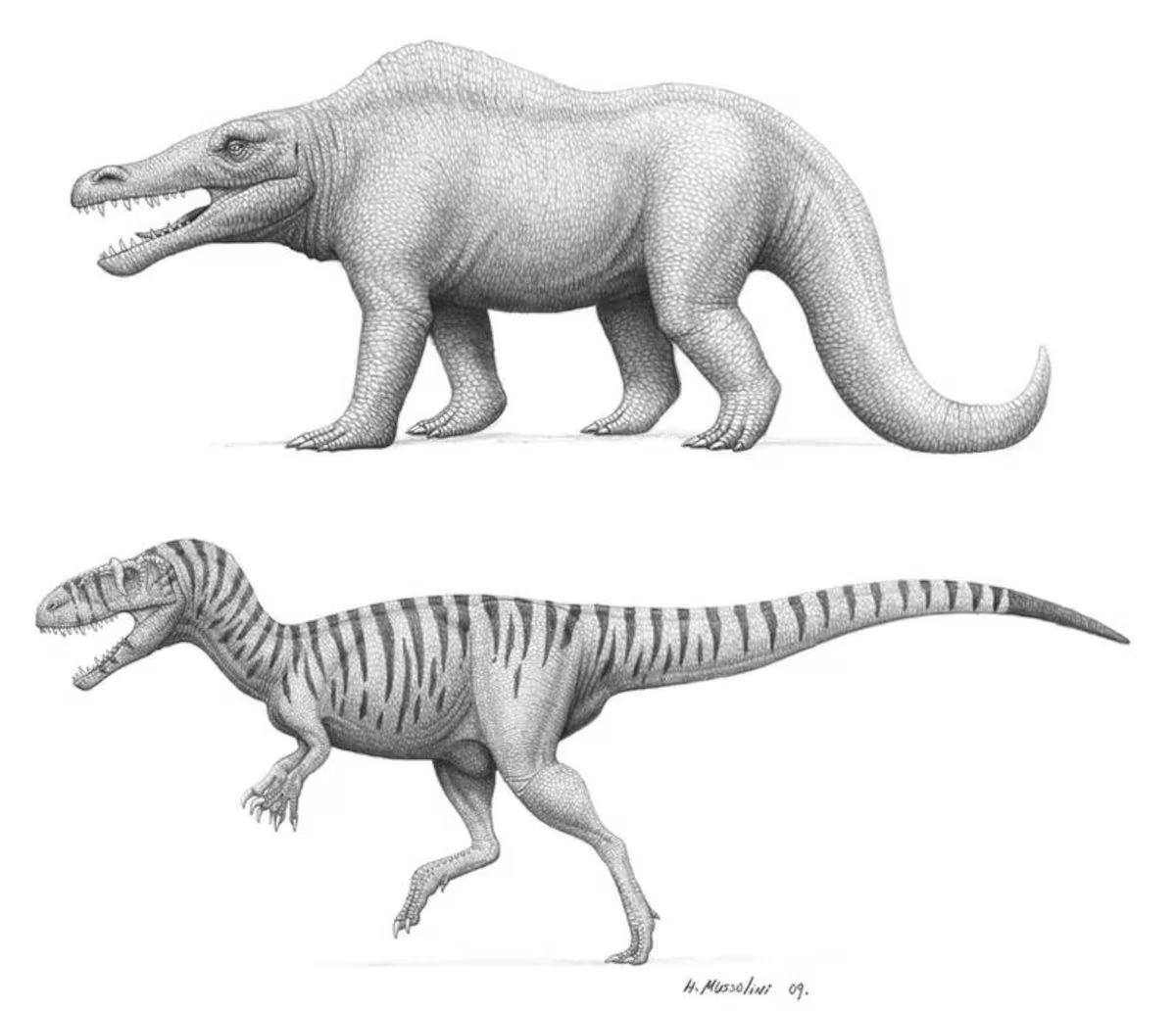

These fish are known as the anthrodires and they included some of the largest and fiercest predators of the time. The poster child for the anthrodires was a monster called Dunkloesteus terrelli, a four meter long armoured fish whose head was covered in bone and who bit its prey with razor sharp bony jaws.

Although discovered in the 1860s there is still much about Dunkloesteus that paleontologists didn’t know. However the last scientific paper on Dunkloesteus was published back in 1932 and paleontology since then has made great strides, especially in instruments. It was certainly time for a new look at Dunkloesteus.

Recently a group of researchers led by Russell Engelman of Case Western Reserve and including paleontologists from Australia, Russia and the United Kingdom have carried out a complete review of all available fossil specimens of Dunkloesteus. What the team found was that Dunkloesteus actually had considerably more cartilage in its bony head than had previously thought, that the muscle arrangement for its jaw was more similar to that of sharks than other fish and that unlike other members of the anthrodires, Dunkloestus really was toothless, making it a real oddball.

My last story concerns what is probably the best known of all extinct species Tyrannosaurus rex. Now finding a specimen of T rex is a rare find, predators are always outnumbered by their prey, there are twenty zebra or wildebeest for every lion in Africa, and when a T rex is found it is usually incomplete. Because of this there can be considerable debate over what a related species or juvenal T rex’s looked like.

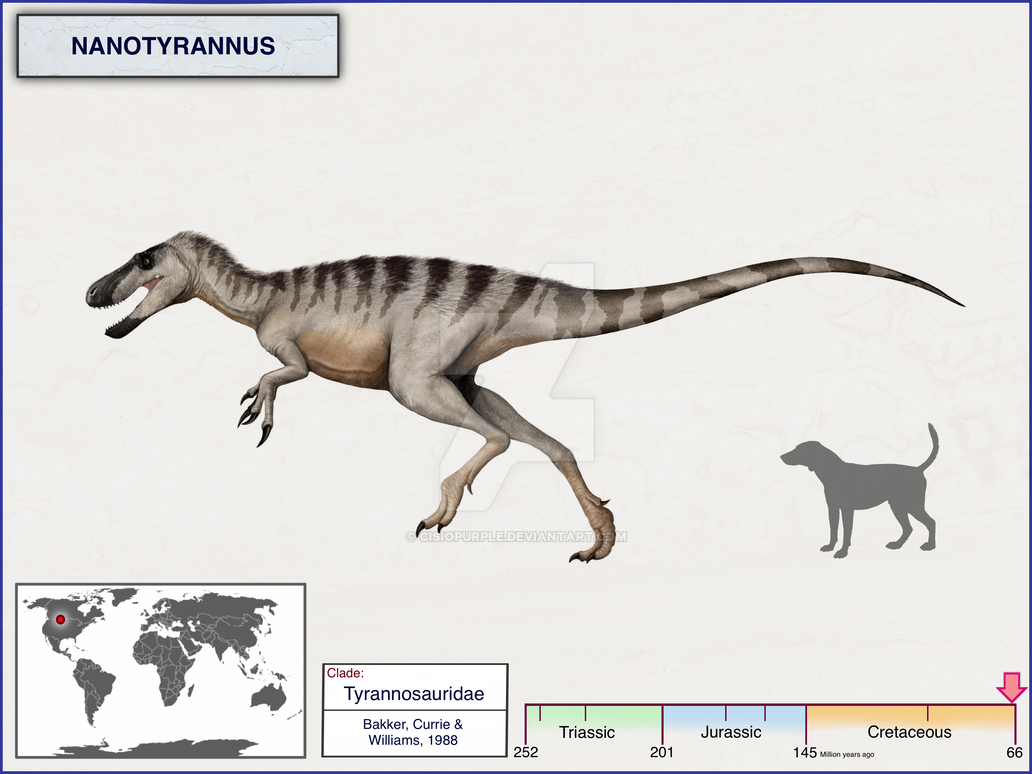

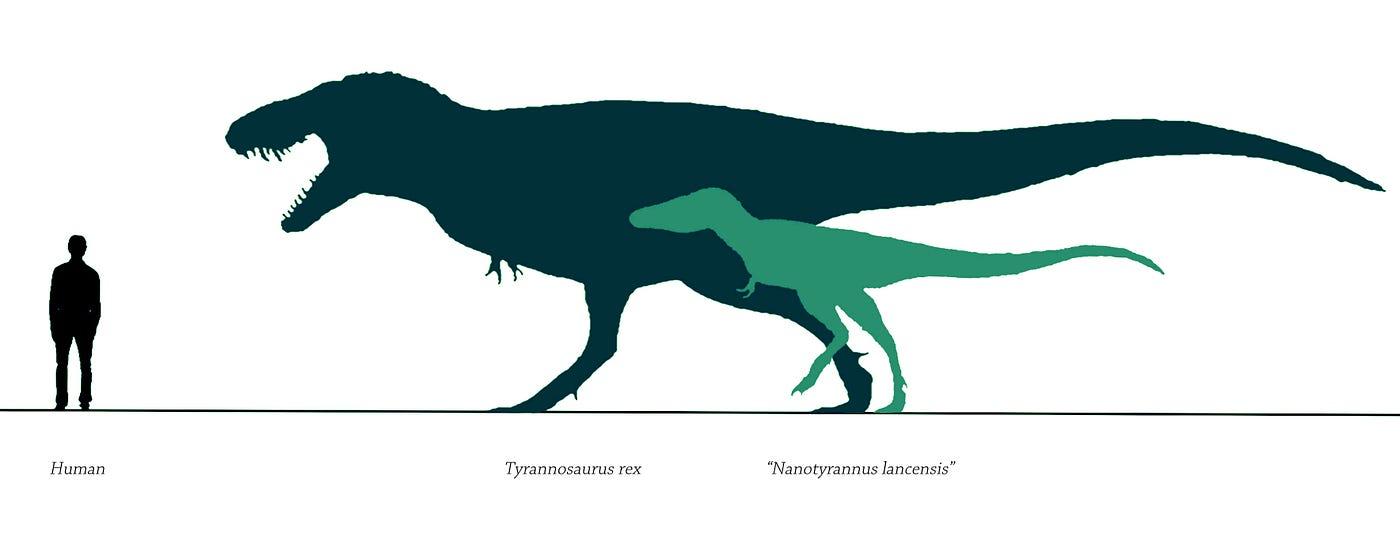

In fact back in the 1980s a skull was unearthed in a rock strata that had already yielded specimens of T rex. The skull was very similar to but much smaller than a T rex skull so initially it was classified as a new species Nanotyrannus lancensis. Then in 1999 another group of researchers re-examined the skull and announced that the specimen was actually a ‘teenage’ T rex. The debate has carried on since then.

Now a through examination of a nearly complete specimen discovered in 2008 may have answered the question. The specimen was of a small ‘T rex like’ animal so determining its age when it died was essential. To do this the researchers cut through the thighbone and counted the growth rings just like a tree. Turns out the animal was twenty years old, hardly a juvenal. Further examination found that the new specimen also had more teeth than an actual T rex would have as well as fewer vertebra in its tail. These details leave little doubt that N lancensis is a true species not a teenage T rex.

In that case however, where are the young T rexes?