Quit a lot happened in space this past month for both manned and robotic missions. While I usually start with the manned missions this month the Lucy space probe made an interesting and surprising discovery so I’ll begin there.

The Lucy probe, launched back on the 16th of October in 2021, is on a mission to study the Trojan asteroids of Jupiter beginning in 2027. For a description of the Trojan asteroids see my post of 6 January 2017. Before reaching the Trojans however Lucy was scheduled to pass by a small main belt asteroid named Dinkinesh, which means, “you are marvelous” in the Amharic language of Ethiopia. It was during the planning for the mission that the engineers at Goddard Space Center decided that Dinkinesh would represent a good opportunity to test Lucy’s cameras and other sensors so the small asteroid was added to the list of asteroids Lucy would study making a total of eight planned flybys at launch.

Turns out that studying Dinkinesh was a great idea because as Lucy passed by on the first of November the images sent back by the probe showed that the small asteroid, about 790m in diameter, had an even smaller moon orbiting around it. While pleased with the surprising discovery the technicians controlling Lucy at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab were equally satisfied at the performance of Lucy’s Terminal Tracking System and it’s Long Range Reconnaissance Imager. Having successfully encountered Dinkinesh Lucy is now ready to begin its prime mission of studying Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids.

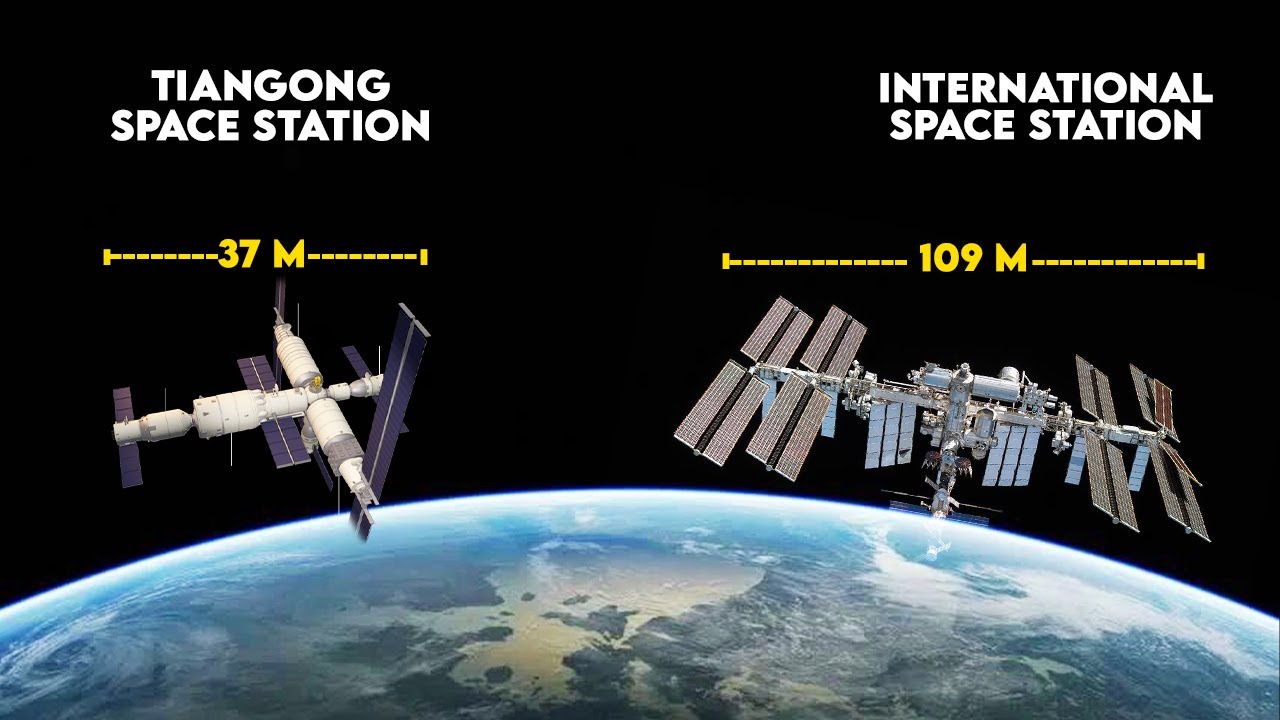

Closer to Earth China has successfully carried out a crew exchange at their Tiangong space station. The station, which is smaller than the International Space Station (ISS), is normally crewed by three taikonauts (as China calls its astronauts). For the past six months it had been the crew of China’s Shenzhou-16 manned mission who had occupied Tiangong but on 26 October China launched the Shenzhou-17 mission from its space port on the isle of Xinhau. A day later Shenzhou-17 docked at Tiangong allowing the Shenzhou-16 crew to return home to Earth, which they did successfully on the 31st of October.

Keep in mind the fact that both NASA and the Russian space agency Roscosmos have carried out dozens of such crew exchanges at the ISS over the last two decades. The fact that China is now keeping its space station manned so smoothly and professionally however is a testament to how far China’s manned space program has come.

Two other news items may tell us something about the future direction of space exploration in the decades to come. The first story concerns Sierra Space Corporation’s long awaited Dream Chaser space plane / mini shuttle. The Dream Chaser design does in fact bear a striking resemblance to the space shuttle and is intended to operate in much the same fashion. Launched into orbit on top of an Atlas rocket or perhaps even a Space X falcon 9 the Dream Chaser would dock at the ISS or another space station. Returning to Earth the Dream Chaser would fly into the atmosphere, experiencing no more than 1.5 g’s in the process and land on a runway like any ordinary plane.

Initially intended to deliver cargo to and from Earth orbit Sierra Space hopes that one day the Dream Chaser will also carry people into orbit. Right now however the Dream Chaser still has yet to fly. Indeed the first Dream Chaser space plane has just recently finished its construction at the company’s factory at Louisville, Colorado, a suburb of Denver. That first Dream Chaser, which has been named Tenacity, will now be shipped to NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Ohio to undergo a series of tests to verify that it is capable of withstanding the rigors of space.

Dream Chaser represents yet another attempt at finding ways to lower the cost of getting into space in order to expand human exploration. Sierra Space Corporation hopes that the first, unmanned flight of this interesting spaceplane could come as early as next year providing some competition to Space X’s Dragon capsule.

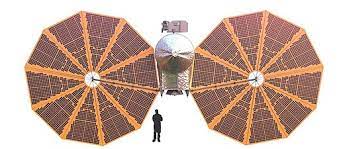

Finally another current limit on our exploration of our Solar System are the low exhaust velocities possible with chemical rocket fuels. I have in several posts discussed both Nuclear and Ion rocket engines which have to potential to provide much greater exhaust velocities and thereby much greater total delta velocities for space travel. See post of 29 April 2020. Recently NASA and the aerospace corporation Aerojet Rocketdyne have carried out a series of tests on the most powerful ion rocket engine ever developed. Known as the Advanced Electric Propulsion System or AEPS the engine operates at a power consumption of 12 kW.

Now ion engines function in a very different way than the chemical rockets we’re used to seeing. In an ion engine the atoms of an inert gas, usually xenon, have an electron stripped from them giving them an electric charge. A high voltage potential then accelerates those ions to a velocity that is scores if not hundreds of times faster than the atoms in a chemical rocket. As the ions are fired out the engine, giving it a thrust, the electrons are reattached to the atoms because otherwise the engine, and the space ship connected to it would quickly build up a tremendous static electric charge.

One major difference between a chemical and an ion rocket engine is that while a chemical rocket gives a big thrust for a few minutes, the first stage of a Space X Falcon 9 only fires for about four minutes, an ion engine gives a small thrust, but it can do so for days or weeks or even years.

NASA has used ion engines in past missions, notably the Dawn deep space probe to the minor planet Ceres and the large asteroid Vesta along with the recently launched Psyche space probe. The space agency hopes to use AEPS on the Gateway space station to be placed in Lunar Orbit sometime around 2025.

Plans for the future even as we have successes in the present, that’s progress in our exploration of space.