Former New York Times science reporter turned author, Dava Sobel has become a popular advocate for the understanding of science through the telling of it’s history. In her earlier books ‘Longitude’ and ‘Galileo’s Daughter’ Ms. Sobel showed how, through science single individuals could change the world.

In ‘The Glass Universe’ Ms. Sobel tells the story of the female ‘computers’ who worked at the astronomical observatory at Harvard University between the years 1880 and 1950. The contributions of these poorly paid, often ignored and rarely appreciated geniuses played a significant role in shaping the way we view the Universe today.

Ms. Sobel starts the story with Dr. Henry and Mrs. Anna Draper, amateur astronomers who have taken an interest in two of the cutting edge astronomical techniques of the time, astrophotography and stellar spectra. (Stellar spectra by the way is using a prism to break the light coming from a star into a rainbow, this spectra will show the spectral lines of the elements within that star) Henry Draper had set for himself the task of photographing the spectra of as many stars as he could.

The Drapers contact one of the leading astronomers of the day, Edward Pickering, newly appointed head of Harvard University’s observatory, for advice but Henry Draper died before he could make any real observations. Feeling that she was unable to continue the work herself Anna Draper instead endowed Harvard Observatory, and her friend Dr. Pickering with a generous fund to carry on the work her late husband had hoped to do. In time Mrs. Draper’s generosity will lead to the acquisition of half a million photographic astronomical plates along with the compilation of the all of the data they contain.

Now in the late 19th century a computer was a human being who carried out the drudgery of long mathematical calculations or tabulations. Every scientific labouratory or observatory had at least a few of these computers, who were normally young male students. Harvard observatory however already had a few female computers; they were cheaper than their male counterparts, and with Mrs. Draper’s endowment Pickering hired several more to assist with the recording of the data on all the photographic plates he and the other male astronomers were taking.

Before long however, the ladies were making discoveries of their own from within all of the data they were recording. Williamina Fleming for example discovered over three hundred variable stars along with ten novas. Then there was Annie Jump Cannon who in the course of her career analyzed the spectra of more than a million stars and who invented a system for classifying stars that with only a few changes is still in use today.

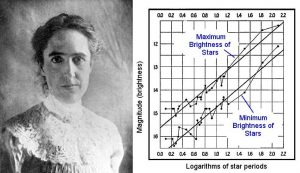

Also there was my favourite, Henrietta Swam Leavitt who studied those variable stars that exhibited a steady, rhythmic pattern. These stars were called Cepheid variables because the brightest such star in our sky is beta in the constellation Cepheus. In photographic plates from Harvard’s southern hemisphere observatory in Peru Ms. Leavitt discovered about 150 such stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud. By recording the period, maximum and minimum brightness of each of these stars Miss Leavitt uncovered a relation between brightness and period that allowed astronomers to use the Cepheid variables as yardsticks for measuring distances throughout the Milky Way and into other galaxies.

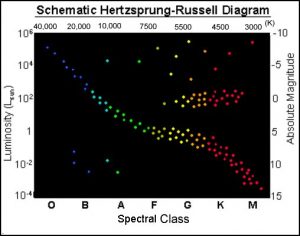

But don’t get the idea that ‘The Glass Universe’ is only about the female astronomers, we get to meet and learn about some of the best known male astronomers of all time as well. Men like Ejnar Hertzsprung who discovered both giant and dwarf stars and was the first astronomer to use Henrietta Leavitt’s Cepheid yardstick. Or Henry Norris Russell, who studied the composition and evolution of stars. These two men are often thought of as a pair because they both worked, independently on what has become known as the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram of stellar evolution. Then there is Harlow Shapley who became director of Harvard University after the death of Edward Pickering and who used Henrietta Leavitt’s yardstick to determine the size of our Milky Way and our Sun’s position in it.

Then there was Solon Bailey who studied globular clusters. Oh, and I can’t forget Edwin Hubble who used Henrietta’s yardstick (are you getting the idea that Henrietta’s work is really important) to measure the distance to the Andromeda Galaxy, proving that it was outside the Milky Way and a galaxy in its own right.

Still, ‘The Glass Universe’ is really about those poorly paid, often ignored and rarely appreciated geniuses who, as Dava Sobel put it “Took the Measure of the Stars”. I’ve know about these great discoveries, both those by the woman and the men, my entire adult life. For me therefore, the delight in reading ‘The Glass Universe’ was in seeing how all of these scientific advances fitted into one another, how the researchers worked together, or occasionally against each other, to give us a new view of our Universe.

I heartily recommend Dava Sobel’s ‘The Glass Universe’. Without doubt it is one of the best books about science and the way human beings do science that you will ever come across.