During all of the celebrations leading up to the 50th anniversary of man’s first landing on the Moon this year I was reminded of another field of scientific exploration that made a lot of news in the 1960s but which has sort of disappeared since then. I’m talking about the idea of people living and working under the oceans and seas of our world, about the possibility of even building underwater cities to colonize the continental shelves that surround the continental landmasses of the Earth.

You think that sounds like science fiction, well wasn’t space travel back then! In fact during the early 1960s the two exploratory efforts of outer space and inner space moved forward in a kind of parallel path. In fact in 1961, the same year as the flights of Yuri Gagarin and Alan Shepard, US Navy diver Robert Stėnuit became the first aquanaut to spend more than 24 hours at a depth of 60m in the ‘Man in the Sea’ project.

To compliment the space race between the US and Russia there was even an ‘Undersea Race’ between the US and France. That’s right France, in the person of Jacques-Yves Cousteau the developer of the Self Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus or SCUBA gear. So many of my generation fondly remember Cousteau both from his articles in the National Geographic magazine along with his TV show filmed aboard his ship the Calypso so I’ll talk about his Continental Shelf or ‘Conshelf’ project first.

Cousteau’s program began with Conshelf I in 1962 with two men spending a week at a depth of 10m in the waters off the French city of Marseille. The Conshelf I habitat was a simple pressurized cylinder with an egress hatch that allowed the two man crew to work outside in the water for a minimum of five hours a day. See image below of Conshelf I being readied for installation.

Then in 1963 Conshelf II was much more ambitious, with two occupied structures and even an underwater garage for a small two-man sub. The larger habitat, see image below, was a starfish shaped base where six men lived and worked for a month. Near the starfish was the round garage for the sub. There was also a smaller two-man cabin at a depth of 25m. The second image shows the basic setup of the entire Conshelf II project.

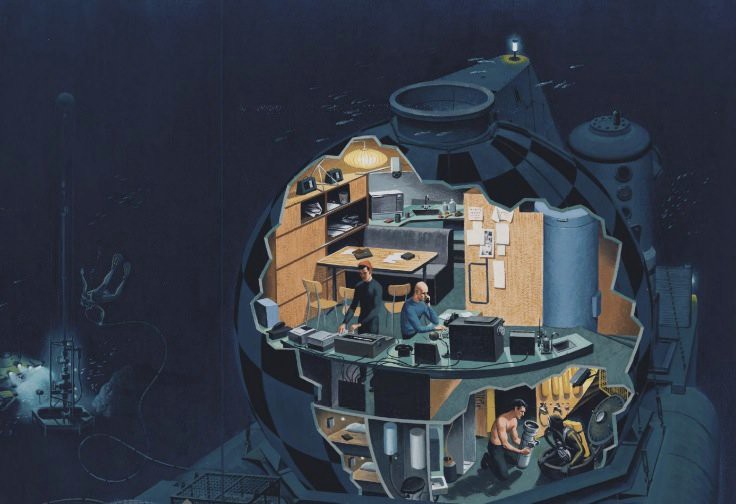

Conshelf III was Cousteau’s final, most ambitious attempt at living in the depths of the sea. In 1965 six men lived inside a spherical shaped pressure vessel at a depth of over 100m for three weeks. See image below. One of the ways in which Conshelf III was more difficult was that, whereas Conshelf I and II and received power and supplies from the surface Conshelf III was mostly self-sufficient, with few ties to the surface.

Originally Cousteau had planned on continuing the Conshelf project with two more underwater habitats but Conshelf III was to be the French oceanographer’s last project for living on the ocean’s floor. In his three Conshelf experiments Cousteau demonstrated man’s ability to live and perform useful work while living inside the ocean.

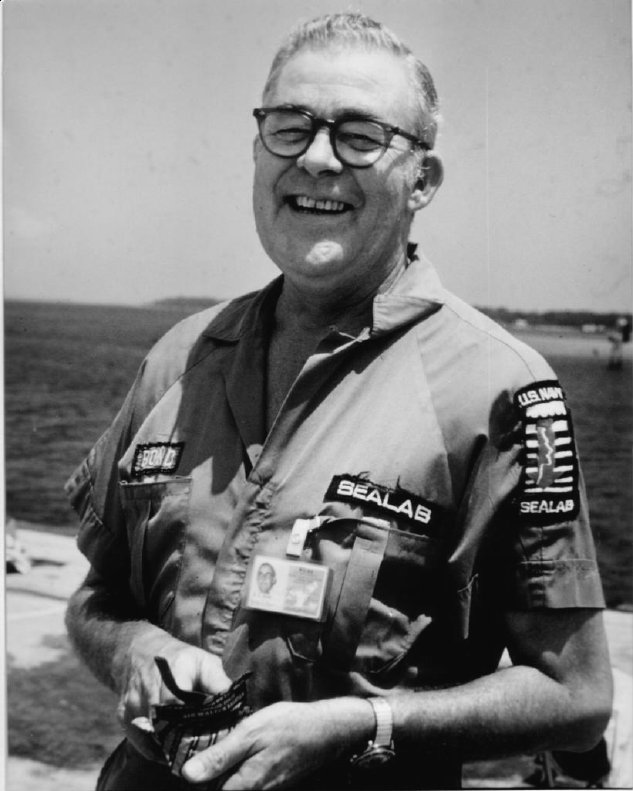

Meanwhile the US Navy was conducting a program of its own in underwater habitation under the project name Sealab. The man in charge of Sealab was Dr. George F. Bond, a modest country doctor from North Carolina who had been drafted during the Korean War and quickly became the head of the Navy’s Medical Research Laboratory. Under Dr. Bond the laboratory led the way in studies of breathable gas mixtures that could allow humans to work for longer periods of time at greater depths underwater.

The Navy’s goals in the Sealab program were slightly different that those of the French. The Navy was more interested in perfecting the techniques of deep diving while at the same time studying the psychological and physiological effects of isolation at great depth.

Sealab One, see image below, was placed at a depth of 58m off the coast of Bermuda in 1964. The plan was for four men to live inside the Sealab module for three weeks but due to an approaching storm the mission was cancelled after only 11 days.

Sealab Two, see image below, took place the following year in 1965 and was much more successful. Placed off the coast of California at a depth of 62m it was manned by three separate teams of divers. Each team of nine men spent 15 days in the habitat but one of the team members, Mercury Astronaut Scott Carpenter spent a record 30 days in the lab. Another interesting aspect of Sealab Two is that a bottlenose dolphin named Tuffy who was an experimental animal with the US Navy Marine Mammal Program assisted the human team members in their work.

Sealab Three, which was lowered into 185m of water off San Clemente Island California, followed in 1969 using a refurbished Sealab Two habitat. Five teams of nine divers were planned for the program but the greater depth of Sealab Three caused problems from the very beginning. These problems in fact led to the death of aquanaut Berry L. Cannon when his rebreather failed to remove the carbon dioxide from his exhalation.

It’s obvious that with the Conshelf and Sealab programs considerable progress was being made in learning how to live and work on the seafloor during the 60s. So what happened? Why haven’t we gone further? Shouldn’t there be cities, or at least towns on the seafloor by now?

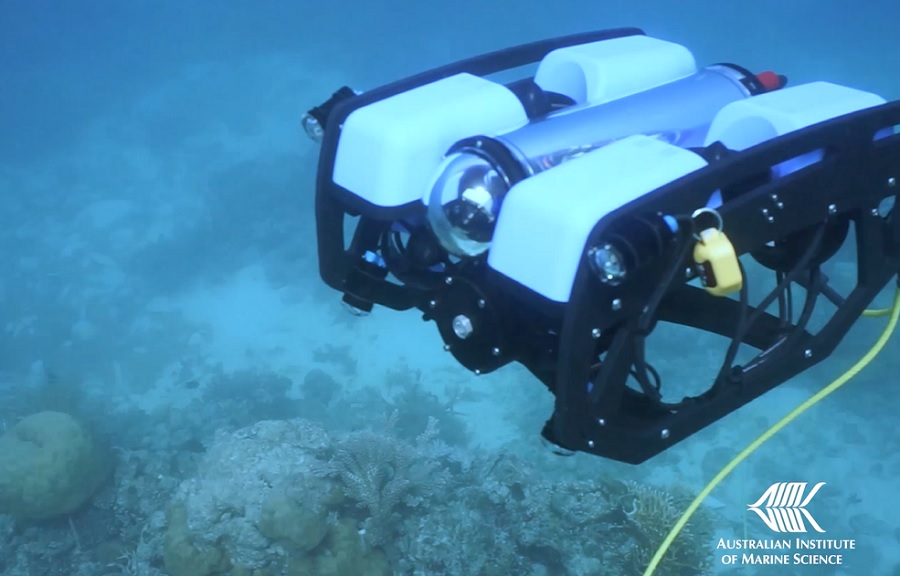

The reasons for why undersea habitats didn’t progress any further are pretty much the same as the reasons for why human exploration of space has also slowed to a snail’s pace. One reason is robots. Just as robotic space probes have explored every planet in our solar system more cheaply and safely than humans can, so undersea robots are doing many of the jobs it was once thought humans would do. Then of course there’s the difficulty of money. Big science, whether in space or under the sea, just doesn’t get funded the way it once did.

However both of those reasons are just symptoms of the real reason, a lack of interest by the general population. There was a time when moving into space or into the oceans was considered a logical next step. We had explored and settled all of the land areas of the Earth so it was just natural that we would move on to explore the sea and sky. That kind of logic just isn’t popular anymore. Maybe it will become so once more. I hope so because the idea of living under the sea, like living in space was a lot more fun than the endless bickering we seem to waste all of our time on nowadays.